Nova Scotia schools will get a new school code of conduct, which gives teachers a guideline for how to respond to violent incidents.

The government hopes standardizing the response will help reduce the amount of violence in schools.

School violence has been rising in Nova Scotia in recent years, and many teachers have voiced their concerns about the previous code of conduct. It lacked standardization, which prevented teachers from accurately and efficiently reporting incidents.

Educators will have several professional development days and training opportunities to learn about the new code of conduct before it takes effect for the new school year in September.

The new code of conduct was delayed several times, but Education Minister Brendan Maguire says he wanted to make sure they did it right before releasing it. The province has also been working on it since before he took over the role as Minister of Education. Becky Druhan was the previous minister for the department, and in October 2024, she said they were doing consultations on a draft of the policy.

Alleviating some work from teachers

Amy Hunt, chair of the School Administrators Association of Nova Scotia, says the new code of conduct is much appreciated.

“One thing I’m really excited about is the emphasis on this being a shared responsibility of all members of the school community,” says Hunt.

With the previous code of conduct, all the responsibility to report violent incidents fell on teachers, but under the new one, other school staff will also be able to report.

New equity and trauma considerations

There were also barriers when teachers would report violent incidents in PowerSchool. They could not identify if a student had special needs, was a visible minority, or the student’s gender and name. Reports also did not have options to show if staff or students were victims of violence, according to a report from Nova Scotia auditor general Kim Adair.

But with the new code of conduct comes a new way to report incidents.

The PowerSchool system will be adapted to allow more information to be reported. The responses to violent incidents will consider a variety of factors affecting a student, including trauma, disabilities, mental health needs, and more.

“I particularly appreciate the lens of equity and taking restorative approach and a trauma informed lens, because those of us who work in schools every day know that it’s a very complex place to be,” says Hunt.

Standardized response to incidents

The previous code of conduct lacked a clear guideline for how to respond to incidents, which was one of the biggest concerns from teachers and staff who wanted to reduce the amount of violence in schools.

The new code offers a more clear guide, both in terms of consequences for students and other responses, like connecting them to support systems, councilors, or adding learning materials to the curriculum.

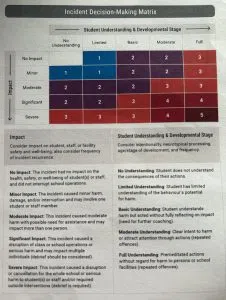

The province has created what they call an incident decision-making matrix.

A photo of the decision-making matrix, which standardizes how teachers and school staff will respond to violent incidents in schools under the new code of conduct. (Nova Scotia Government)

Teachers and staff will gauge the severity of the response based on the metrics in the matrix.

It considers the impact on students and staff, as well as how much the student should be able to understand the consequences of their actions.

Each number/colour corresponds to a consequence:

One: in-school suspension

Two: less than 3 days suspension

Three: 3 to 5 days suspension

Four: 5 to 10 days suspension

Five: 10 or more days suspension

During a technical briefing, government officials cited an example of what would happen to two Grade 9 students who hypothetically got into an argument and then a fight in a school cafeteria.

The students are old enough to understand their actions, and because many students saw it, there was a large impact on the school. Based on that, they say it would qualify as a four on the scale, which would be 5 to 10 days suspension.

On top of the suggested consequences, there are suggested responses. Under the physical violence category, that includes teaching students to manage disagreements constructively, small-group sessions on managing anger, or working with the student’s family or community support to create a plan to address violence. There are several categories, each with their own tailored responses.

“As school and system leaders, we appreciate the guidance and the consistency and the intent. We are committed to helping with the professional learning, because our members will be leading that work in our public schools,” says Hunt.